On Friday I had the privilege of speaking at the AIPLA Spring Meeting in Los Angeles on the subject of pre-1972 sound recordings and the current series of lawsuits brought by the successors of the Turtles against Sirius XM regarding royalties over pre-1972 sound recordings. Copyright law in the United States is almost exclusively governed by the federal Copyright Act, which preempts equivalent state laws. As originally drafted, however, federal copyright law did not extend copyright protection to sound recordings, leaving those works to be regulated by the states. Congress amended the copyright law in 1972 to add federal protection for sound recordings, but it granted this protection on a prospective basis only. Sound recordings fixed before February 15, 1972 thus remain subject to state law. A series of lawsuits brought by Flo & Eddie, Inc. (“Flo & Eddie”), the entity that owns the copyrights for sound recordings created by the 1960s rock group the Turtles, is upending rules thought long established regarding performance rights of pre-1972 sound recordings under state law. Continue reading

From “Happy Together” to “Eve of Destruction”

Pennies Not From Heaven

Aereo settles broadcasters’ claims in bankruptcy

Aereo Inc. has reached a proposed settlement with the broadcasters that have sued it for infringing their copyrighted works. The settlement would result in payment of $950,000 to the broadcasters in satisfaction of their claims seeking over $99 million – amounting to less than a penny on the dollar.

This development follows lengthy legal proceedings that saw the dispute go all the way to the Supreme Court on the issue whether Aereo was publicly performing the plaintiffs’ television shows, originally broadcast over the air for free, by streaming them to subscribers over the Internet. Section 106 of the Copyright Act reserves to the copyright owner six exclusive rights, including the right to publicly perform literary, musical, dramatic and motion picture works. In the so-called “Transmit Clause,” the statute provides that “to perform or display a work ‘publicly’ means … To transmit or otherwise communicate a performance or display of the work . . . to the public, by means of any device or process, whether the members of the public capable of receiving the performance or display receive it in the same place or in separate places and at the same time or at different times.” 17 U.S.C. § 101. The Transmit Clause was added to the Copyright Act when it was amended in 1976 as a result of two Supreme Court cases: Fortnightly Corp. v. United Artists Television, Inc. and Teleprompter Corp. v. Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc. In those cases, the Court had held that community cable systems that retransmitted free, over-the-air broadcast signals did not “perform” the copyrighted works in the broadcasts and did not infringe the copyright owners’ public performance rights. Congress added the Transmit Clause to the 1976 Act to overturn these decisions. Continue reading

Pandora’s Box:

Turtles Actions Threaten to Upend Music Streaming Models

Copyright law in the United States is almost exclusively governed by the federal Copyright Act, which preempts equivalent state laws. As originally drafted, however, the Copyright Act of 1976 – the current iteration of the Act – made an exception for sound recordings fixed before February 15, 1972, leaving those works to be regulated by the states. State law thus applies to determine the rights and remedies available to the copyright owner of pre-1972 sound recordings. Continue reading

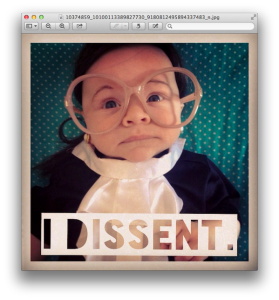

Have a Noninfringing Halloween

Name That MP3Tune:

Denial Ain’t Just a River in Egypt

Breaking: This morning, Judge Pauley of the Southern District of New York issued an opinion granting in part and denying in part (but mostly denying) the defendant’s motion for judgment as a matter of law in Capitol Records v MP3Tunes, in which the jury had found liability for copyright infringement and awarded over $48 million in damages. The opinion is lengthy and fascinating, especially in its characterization of the parties, and particularly the defendant. This post summarizes the rulings on each issue and sprinkles in some of the court’s more colorful commentary. Continue reading

Shades of Gray Takes the Ice Bucket Challenge

Or, How

Copyright Lawyers Do It

Today, Shades of Gray took the Ice Bucket Challenge in true copyright lawyer fashion – with a sprinkling of copyright (and comments from the Harvey Siskind peanut gallery). Happy Friday!

The Seventh Circuit Is Not Impressed

Transformativeness? Whatevs

The Seventh Circuit is not impressed with the transformative use doctrine (cue graphics of Judge Easterbrook wearing a McKayla Maroney frown). The court just issued an opinion giving the back of its hand to transformativeness, acknowledging only that the Supreme Court “mentioned it” in Campbell. Nonetheless, the court granted summary judgment to the defendant on the ground that its antiauthoritarian poster did not interfere with the market for the plaintiff’s photograph under fair use factor 4. Kienitz v Sconnie Nation LLC, issued today.

Monkey Shoot, Monkey Speak:

The Monkey Weighs In

I was indescribably relieved upon returning from my summer vacation to discover that we have not yet finished discussing the Monkey Selfie. No bona fide copyright lawyer could possibly want to see an end to this dispute. You can imagine my joy, then, when both the Copyright Office *and* the monkey himself (herself?) recently weighed in on the issue.

The Copyright Office issued a draft of the Compendium of Copyright Office Practices (3rd ed.) on August 19. The Compendium – a monumental undertaking – documents and explains Copyright Office practice and procedure, including with respect to registering claims to copyright. Chapter 300 addresses “Copyrightable Authorship: What Can Be Registered.” At Section 306, the Copyright Office clearly states, “The Office will not register works produced by nature, animals or plants. . . . Examples: A photograph taken by a monkey.”

Bananas! The monkey says. Perhaps counseled by the Cave Man Lawyer (h/t @boothsweet), and apparently having learned English from Cookie Monster, the monkey has his own highly entertaining views on the matter, which you can read here.

So Easy a Monkey Can Do It

To the delight of copyright lawyers everywhere, yesterday the infamous Monkey Selfie debate of 2011 revived itself in the wake of a transparency report issued by Wikimedia revealing that the organization refused a request by photographer David Slater to remove the photo from Wikimedia Commons. Slater traveled to Indonesia in 2011 to photograph macaque monkeys. By Slater’s own account, a monkey grabbed one of his cameras and began snapping photos, including this one . Slater apparently licensed the image for distribution, and later discovered that it had been uploaded to the Wikimedia Commons database. He demanded that Wikimedia remove the image, and the organization refused on the ground that Slater did not create the image himself and therefore does not own copyright in it. Slater’s demand, and Wikimedia’s refusal, came to light when the organization issued its transparency report. Copyright Twitter feeds everywhere immediately lit up like a Christmas tree.

Under U.S. copyright law, the author of a work is the one who created it. In wonky copyright terms, it is the person who fixed an original expression in a tangible medium. Here, Slater has publicly admitted that he did not create the photograph; the monkey. The United States Copyright Office takes the position that only human beings can be “authors.” Animals need not apply. Accordingly, this gives rise to the somewhat unusual situation where there appears to be no author as a matter of law, and thus no copyright ownership.

Of course, U.S. copyright law generally does not apply extraterritorially, and the image in question was created in Indonesia. Although both countries are signatories to the Berne Convention, which requires member nations to give each others’ nationals equal treatment under copyright law, the question of who owns the copyright in the image in the first instance may be governed by Indonesian law.

Slater has reportedly consulted with a U.S. attorney, and is supposedly considering pursuing an infringement action.

Last Call: Orphan Works and Mass Digitization

The Copyright Office is now accepting further public comments on the issue of orphan works and mass digitization. The Office held public meetings earlier this month, which, by various accounts, were heated at times. Interested members of the public wishing to submit comments can find more information and the electronic submission form here. Comments are due by April 14, 2014.